Damien Hirst at 60: Vision for Art Beyond His Lifetime

Within the esteemed Albertina Modern in Vienna, a notable art museum, resides a modest pencil sketch depicting a cabinet and a medicine bottle. Alongside it flows a series of intriguing words and phrases such as “God,” “Anarchy,” “Bollocks,” and “You’re only 29. You’ve got a lot to learn.” This exhibition showcases Damien Hirst’s artwork, presenting a retrospective journey from 1987—when Hirst was an art student—up to contemporary creations. More than just a display, the exhibition opens a window into the psyche and thought processes of the influential artist.

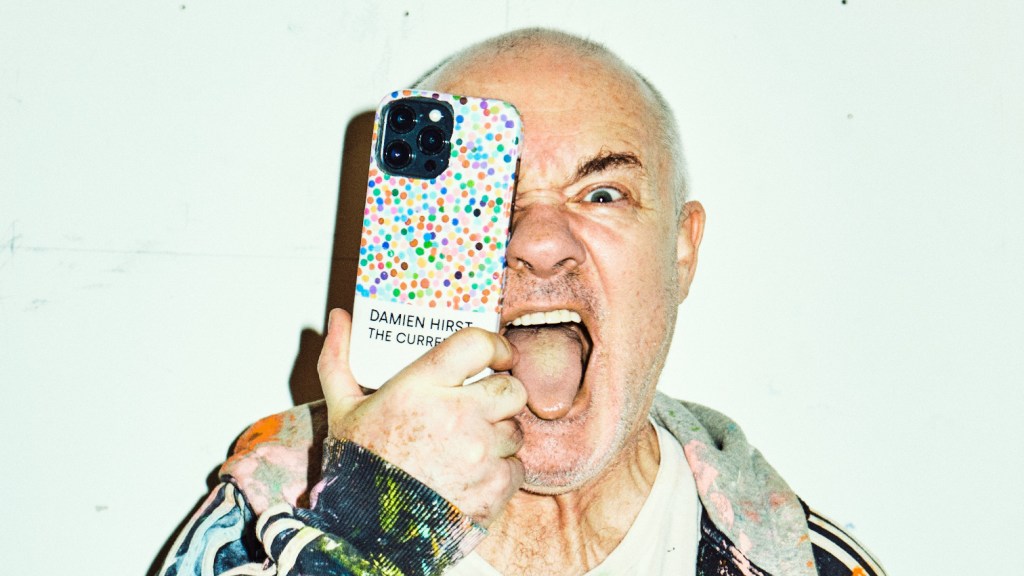

Days later, I delve deeper into this exploration during a Zoom interview with Hirst. He appears from a plain hotel room furnished with dark decor and crisp white bedding—an unexpected setting for one of Britain’s wealthiest living artists. His location?

“Las Vegas. London’s been a bit gloomy lately, and my partner [Sophie Cannell, a former ballerina] enjoys it here. We also have a new baby, Noah, and there are countless mother and baby gatherings,” he shares.

As Hirst approaches his 60th birthday next month, he reflects on his life and career. During nearly two hours of conversation, we cover topics ranging from existence and mortality to his experiences as a father and the monetary aspects of the art world. A striking element of our discussion involves his concept of “posthumous drawings”—plans for art that can be created and sold under his name for up to 200 years after his passing, to be signed by his descendants. With Hirst, it often blurs the line between seriousness and humor.

Critic Waldemar Januszczak argues that Hirst’s impact is unparalleled, suggesting that without him, movements such as the Tate Modern, the Young British Artists (YBAs), and even Cool Britannia might not have emerged. His breakthrough occurred in the late 1980s when, as a second-year student, he organized the notable “Freeze” exhibition, showcasing the work of 16 Goldsmiths students in a vacant structure in London’s Docklands. This event drew the attention of art collector Charles Saatchi, who sold off pieces from his postwar American collection to invest in Hirst and his peers. Saatchi’s support propelled a series of exhibitions in the early ’90s, including Hirst’s iconic “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” which featured a preserved shark in formaldehyde—a piece that captured global fascination and cemented Hirst’s historical significance in art.

Hirst reflects on his discontent with the art scene preceding Britart in the 1990s, stating, “The trend was for untitled pieces, and I found it frustrating. I believed art had deviated from its path since the ’50s or ’60s, and it needed revitalization.”

He emphasizes the importance of titles and how his controversial presence brought contemporary art to a wider audience. Hirst recalls, “I enjoyed the conversations with cab drivers who’d say, ‘Are you that Damien Hirst geezer?’ When I’d confirm, they’d say, ‘I saw your dead sheep, and it was quite good.’”

Hirst has long sparked debate over his methods, facing accusations from plagiarism to the operations of his art factories, which employ numerous assistants. His venture into digital art, termed “The Currency” in 2022, was perceived by some as a quick profit scheme. Recent reports also suggested Hirst backdated three installations, initially created in 2017, to the ’90s, which led him to argue that the concept behind the art mattered more than its timeline—much like Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons before him.

Despite an estimated fortune in the hundreds of millions, Hirst hasn’t aligned himself with the traditional art establishment like some of his contemporaries (Dame Rachel Whiteread, Dame Tracey Emin). He expresses regret about accepting the Turner Prize in 1995, stating, “Art is incredibly difficult to judge, and there are no genuine criteria for selecting winners.”

When questioned about a potential knighthood, Hirst admits he hesitated, explaining, “In a way, yes. They tend to gauge your interest before presenting it. I had a conversation with Jacob Rothschild, who had been visiting my home and studio. One day he offered me a CBE, which I declined, followed by a KBE which I also turned down. Why? I didn’t feel comfortable with the idea.”

Discussing the notion of home, Hirst seems uncertain. He once owned a farmhouse in Devon, but reveals that his three older sons have “taken it over,” now requiring him to schedule time to use it. He possesses residences in Mayfair, Richmond, and the Cotswolds, stating, “I used to buy everything, like Monopoly—buying places I’d stay while on holiday.”

Hirst previously spent considerable time in Mexico, where he owns properties, but his partner, Cannell, dislikes visiting due to concerns over spiders and other creatures. “She hates tarantulas, and we even had a crocodile in the pool, so that’s off-limits now,” he quips.

Open about his affinity for wealth, Hirst often faces criticism. He believes that money plays a crucial role in today’s world. “Staying aware of the market and preventing unsold artwork is vital. I’m fortunate to have a capable business manager who collaborates on ideas with me,” he states.

Hirst’s early experiences selling items at his mother’s market stall sparked his interest in trading. “My mum also painted and inspired me to draw—she’d always provide me with fresh paper after I completed a piece,” he recalls.

Influential figures in his life included his art teacher, who also managed the school’s theater group. Hirst contemplated acting after portraying Bottom in a school play of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” but ultimately chose art school instead, desiring authenticity in his expression.

Frequent visits to the Leeds Museum during shopping excursions with his mother also shaped him. “Upstairs they displayed works by Peter Blake and Francis Bacon, while downstairs featured an aquarium and a giant Bengal tiger. Natural history museums offer wonder accessible to everyone, unlike some art museums that can feel pretentious.”

During the peak of his career, Hirst employed around 350 individuals. “I currently employ about 150 but produce three to four times as many artworks,” he claims, reflecting on his growth in business acumen. Initially worried that engaging with business would detract from his artistry, he now finds enjoyment in it.

When asked if he views himself as a CEO, he responds, “I also have a therapist.” Initially focusing on personal relationships, their discussions have evolved to include issues within the art world and interpersonal dynamics with his staff.

Struggling with the challenges of managing a creative team, he shares insights from his therapist about “the sacred” concept in art. His team must perceive their labor as contributing to sacred creations.

Contemplating the art market’s inconsistencies, Hirst muses about the perceived values of paintings versus the costs of production. “Artists like Picasso command astronomical prices despite minimal material costs. In my case, when it comes to expensive works, suspicions arise—like with my diamond skull piece, “For the Love of God,” priced significantly higher than the sum of its materials. In 2007, it was reportedly sold to a consortium that included me, but later I suggested no actual sale occurred.

Referring to a 2022 New York Times article suggesting he was losing influence in the art market, I ask if this concerns him. He responds, “Sales remain strong for me. Friends of mine struggle to sell their art. I’ve experienced spikes in pricing, notably during that extraordinary Sotheby’s auction.”

Hirst recalls the unique 2008 auction where he bypassed traditional galleries, resulting in nearly £200 million in sales over two days amidst global financial upheaval—a moment he describes as surreal that boosted his confidence, although he admits his works now sell for less.

Addressing the principle of supply and demand, he reflects on the impact of market saturation on the value of his spot paintings. He derived inspiration for these from a blend of artistic influences and personal experiences, likening them to appealing items for affluent buyers.

Another key inspiration stemmed from his childhood admiration for snooker, nurtured through memories of watching the sport with his grandmother. Meeting champion Ronnie O’Sullivan later formed a friendship, and they share creativity in their respective crafts.

Recently, Hirst has returned to painting, creating expansive floral artworks using a unique dot technique, although he hasn’t produced many lately.

As he approaches his sixties, he senses a shift in the art market due to global uncertainties. He’s reconsidering the scale of his works, suggesting that instead of creating large series, a more limited run of 60 or 40 pieces might be prudent.

Does the milestone of turning 60 concern him? “Not particularly. I’m fortunate in that you can dedicate your entire life to creating art—there’s no stipulated retirement.” He admits he won’t celebrate with a party, as he’s grown distasteful of them after giving up alcohol and drugs. The early years of his career were filled with indulgences, and he recalls a conversation with Blur’s Alex James about the supposed glory days of their youthful escapades, where James summarized it as a nightmare.

After struggling with sobriety for six years, Hirst admits that this change has positively impacted every aspect of his life, including his artistry. He now aims to be a better father, expressing a preference for the title “Dad” over “Artist” on his gravestone. As he nears a new decade, he is concerned about leaving his children a favorable legacy, contemplating how to prepare his affairs for the future. His sons lean more towards music than visual art, although he notes that baby Noah seems to show an emerging interest in creativity, proudly displaying a photograph of his son engaged in drawing.

In the meantime, Hirst contemplates the legacy of his artistry beyond his lifetime. He envisions filling 200 notebooks with sketches and concepts, each representing a year after his demise. His manager wittily refers to these as “preposterous paintings”—a fitting term for his ambitious posthumous pursuits.

The idea is to provide certificates permitting the creation of sculptures based on these drawings, allowing for these creations to be made 145 years after his passing but dated to 1991, as with a conceptual piggy sculpture he envisioned long ago.

Could this concept lead to the trading of art futures? “If it materializes, yes,” he replies, flashing a knowing grin. Given Hirst’s history of audacious concepts, he might just succeed.

As our conversation concludes, he reveals a bandaged arm, a result of a dislocated shoulder from a recent trip to Thailand. “It’s pretty gruesome. I had surgery there, and I’ve now strained another muscle.”

Can he still paint? “Absolutely. I have no issues painting with both my skills and assistance from my team.”

Damien Hirst: Drawings is on display at the Albertina Modern, Vienna, until October 12.

What are your thoughts on the legacy of Damien Hirst and the YBAs? Share in the comments below.

Post Comment