The Importance of Appreciating Philanthropy in the Arts

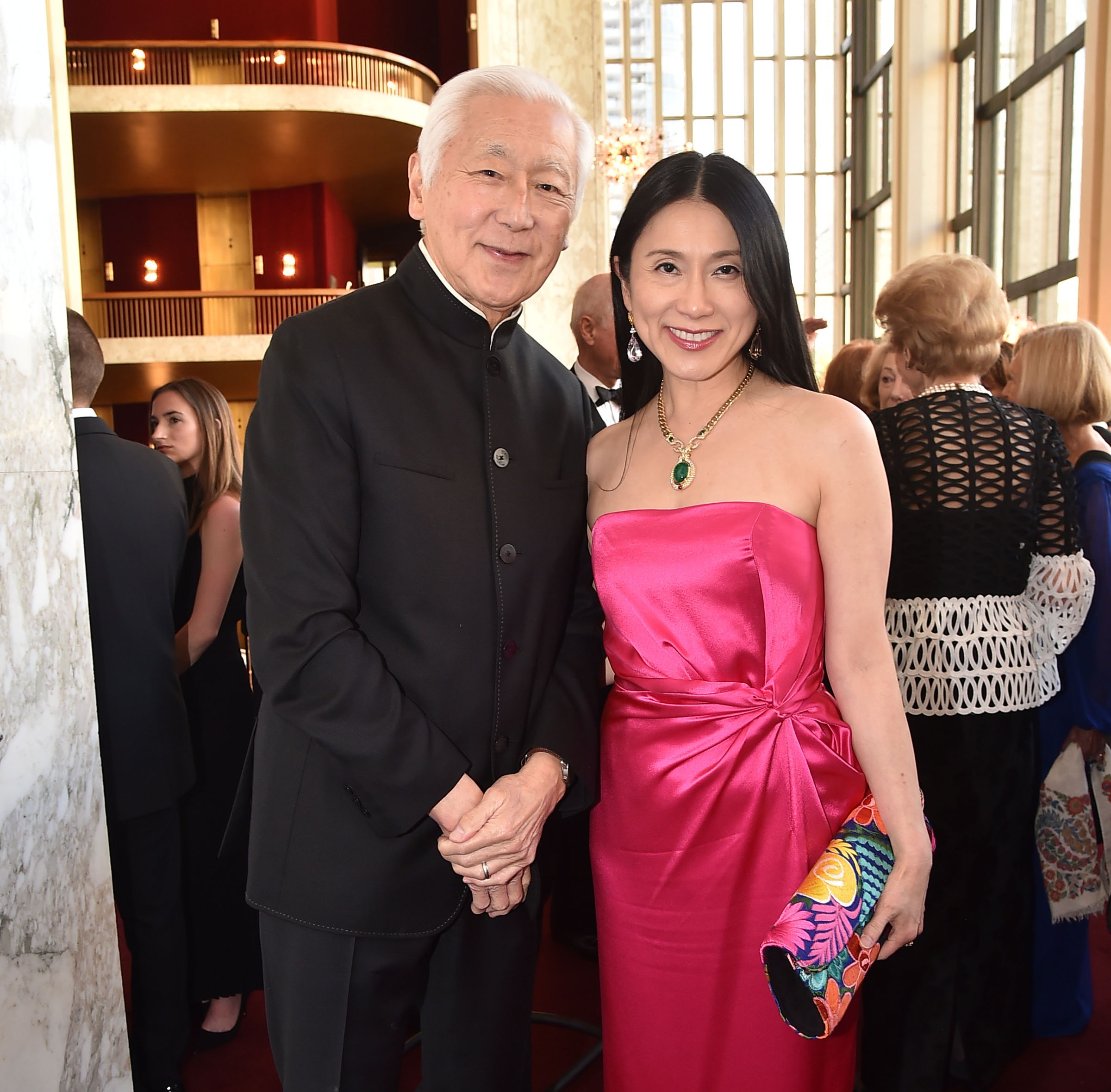

Once again, I find myself amazed at the ease with which American arts organizations secure substantial funding from wealthy donors. This week, a feature in The New York Times highlighted a philanthropic couple, Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang, who are among the most prominent arts benefactors in history.

The Tang name will soon grace the new contemporary art wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York after they contributed a remarkable $125 million (around £100 million) to revive the delayed project. This is in addition to numerous artworks that Oscar Tang has donated to the Met since the 1990s. The New York Philharmonic is also set to welcome the world-renowned conductor Gustavo Dudamel as its music director, thanks to a generous $40 million donation from the Tangs. Furthermore, various universities across the United States have received Tang institutes and museums, owing to substantial contributions over the years.

What drives such remarkable generosity? The answer is rooted in gratitude for their adopted nation. Oscar Tang was just 11 when his family fled Shanghai following the 1949 communist takeover. After arriving in America, he ascended the financial ladder, established his own enterprise, amassed a fortune, and decided to share a significant portion of it with the country that welcomed him. “We’re grateful to be Americans,” he states. Together with Agnes Hsu-Tang, an art historian and archaeologist from Taiwan, he has a knowledgeable partner in their philanthropic endeavors.

The Tangs’ case is not an isolated one. Each visit to New York reveals further examples of how immense financial contributions catalyze swift advancements in the arts. For instance, I attended the grand opening of the Shed, a major arts venue in lower Manhattan, which was entirely funded by private donations totaling $500 million.

Three years later, the Lincoln Center transformed its concert hall, courtesy of a $100 million contribution from entertainment mogul David Geffen. The Tangs are particularly noteworthy because they exemplify how a legacy of first-generation immigrants to the U.S. enriches the cultural landscape.

Immigrants have historically influenced the cultural fabric of the UK as well. The presence of enlightened figures such as Prince Albert in the 1840s led to the establishment of the prominent South Kensington museums. Moreover, the contributions of talented European Jews who fled Nazi persecution significantly boosted Britain’s operatic and orchestral scenes in the mid-20th century.

Many notable British philanthropists of the 20th century were also immigrants or descendants of immigrants, including Paul Hamlyn and Charles Clore, the latter of whom has seen his daughter Vivien Duffield donate over £500 million to cultural institutions. Isaac Wolfson, the son of a Polish carpenter, donated so extensively to Oxford and Cambridge that he became the only individual to have colleges named after him at both universities without being a figure of religious significance.

In contemporary Britain, there are still individuals like the Tangs who have enhanced cultural life through their wealth. For instance, the heirs to the Tetra Pak fortune, Lisbet, Sigrid, and Hans Rausing, have contributed over a billion pounds to charities and cultural organizations. Additionally, the businessman Leonard Blavatnik, who was born in Ukraine, has made significant donations to institutions like Tate Modern and Oxford University.

Another example includes Elena and Alex Gerko, a couple exiled from Russia after opposing Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Alex has amassed significant wealth through his financial trading firm, XTX Markets, and he has supported the London Symphony Orchestra by funding scholarships for young musicians and donating towards the refurbishment of its educational center.

Moreover, they have allocated £25 million toward advanced mathematics classes for British students. Alex Gerko also made headlines by paying £202 million in taxes last year, ranking him among the UK’s top taxpayers.

Britain would benefit from more benefactors like the Gerkos. However, a stark contrast exists between the UK and the U.S. In New York, cultural institution boards often consist largely of major donors, with such positions bestowing social prestige that encourages contributions.

In contrast, UK boards frequently prioritize diversity or political representation over philanthropic experience. This needs a complete overhaul. Donors should be actively involved in the artistic process and are often adept at managing organizations.

Furthermore, gratitude toward affluent benefactors is less instinctual in Britain compared to the U.S. The British skepticism towards wealth, as captured in the saying, “behind every great fortune lies a great crime,” can hinder support for the arts. This perspective is not only predominantly false but also detrimental. Without the contributions of the Medicis, the Renaissance might never have occurred. Our arts sector, too, requires philanthropists to fill the gaps left by declining public funding, or we risk regressing to a cultural void.

Post Comment